Restorying the Landscape: Connecting with Local Ecologies through Outdoor Arts-based Learning at School

This study demonstrates the use of arts-based environmental education (ABEE) practices as a model for interdisciplinary outdoor learning in a schoolyard bird and pollinator habitat garden.

Research Goals:

To demonstrate a visual arts-based approach to outdoor environmental learning that encourages a creative dialogue between children and the local ecology.

To inspire students to find and share their own stories in the landscape.

To generate and collect art-based data in response to the following research question:

What stories does the landscape tell me?

A Brief Review of the Literature

-

The industrial and technological revolutions have estranged children from the evolutionary and socio cultural imperative to connect with the natural world. (Dewey, 1898; Leopold 1949; Wilson, 1984; Louv, 2005; Van Boeckel, 2013). Children spend less time outdoors due to the loss of natural open spaces as a result of development and car use. (Rivkin, 2015).

The effects of the pandemic are still being determined but recent studies point to an increase in time spent indoors on screens for learning and recreation (Wiederhold, 2020; Velde et al.,2021).

Many educators suggest that bridging the disconnect between children and nature can reverse societal and political indifference to environmental degradation. (Dewey, 1898; Wilson, 1984; Louv, 2005; Graham 2006; Orr, 1998, Capra 2005, Van Boeckel, 2013 Rivkin, 2015 , Inwood 2018)

The dramatic decline in wild bird and pollinator populations in recent years is of concern to scientists and naturalists.

-

Research shows that time spent in nature through exploration and play increases children’s sense of well-being and improves their ability to cooperate with peers (Fjortoft, 2004; Charles, 2009; Chawla, 2020). Exposure to nature during the school day boosts academic focus upon return to the classroom. (Fjortoft, 2004; Nedovich; 2013; Lundy et. al, 2020)

In the US, Public Schools own around 2 million acres of land. (https://www.tpl.org/community-schoolyards-report-2021). Schools are in an optimal position to bridge the divide between children and and nature by providing opportunities for outdoor learning on school campuses. There is a lack of documentation of best practices especially at elementary level.

-

Arts Based Environmental Education (ABEE) uses perceptual investigation through the elements and principles of art as a point of departure for understanding ecological systems. (Van Boeckel, 2013; Woolery; 2006;)

Roots in environmental movement of 60s and 70s

American art educators called for a transformative art pedagogy, based on the land art movement of the 1960’s and 70’s which could engage students in environmental issues. (Blandy, et al., 1988; Lankford, 1997; Inwood, 2008)

Place Based Education

Place-based education which emphasizes importance of learning from local ecologies, is supported by the interdisciplinary nature of arts education( Capra, 2005; Sobel 2013; Orr, 2013; Blandy et. al. 1998; Gruenewald, 2003; Graham, 2007).

Systems Theory

The arts are important for understanding natural systems. and “speaking the language of nature” (Capra, 2005).

Arts-based learning fosters empathy for the environment

Art has been shown to facilitate a deeply affective connection with natural places and their non-human inhabitants (Bertling. 2015; Gaylie, 2011; Somerville, 2013).

Art- based eco restoration projects (Hall, 2010; Sommerville, 2010; Schnelner, 2021)

-

Metaphors/Interbeing

Calls for a new land-ethic in education, replacing the resource extraction/ consumerism paradigm with an integrated understanding of local ecological systems. (Orr, 1992; Sobel, 1996; Capra, 2005)

The arts are a stimulus for change in environmental attitudes through the creation of metaphors. (Anderson, 2012).

Metaphors are Spatial Stories

French phenomenologist Michel de Certeau (1984) aligns metaphors to spatial stories based on the Greek word for bus, metaphorai. As such, metaphors in the form of stories have thepower to activate places and give them meaning. Visual images can reflect a dialogue between artist and landscape in which the landscape expresses a narrative (Ponty, 1945; Woolery, 2006; Van Boeckel, 2015)

Decolonizing the landscape

Sarris (2020) describes the indigenous tradition of reading the landscape like a sacred text. Local indigenous knowledge is essential for ecological understanding. (Anderson, 2005; Bequette, 2007; Kimmerer 2013; Carew, 2018; Sarris 2017; Sarris, 2020). The mythology of the Coast Miwok refers to specific local plants and animals (Meriam, 1910; Sarris, 2017)

Visual Media

How do we tell stories visually? Using graphics and comics to illustrate abstract, difficult science principles/global warming Bentz (2020) (Bentz and O’Brien 2019; Dieleman 2017). Sousanis, 2015)

-

Cognition through Drawing

Learning becomes embodied by the physical act of mark making (Sousanis, 2015; Woolery, 2016).

Knowledge is constructed through perception

…as is illustrated by Cezanne’s statement that “the landscape speaks itself in me” ( Ponty, 1945). Also of importance is the idea that perception is fluid, multidimensional, imaginative and fundamental to cognition (Van Boeckel, 2013; Ponty, 1945; Sousanis).

Conception cannot precede execution (Ponty, 1945)

Rationale

Schools are in an optimal position to bridge the divide between children and nature through the restoration of natural ecosystems on school grounds. Despite the growing collection of evidence that connecting with nature during the school day improves children’s sense of well-being and increases focus in the classroom, there is a lack of documentation of best practices for outdoor ecological learning, especially at the elementary level.

Arts-based environmental education (ABEE) provides a practical model for interdisciplinary outdoor learning on school grounds. ABEE develops deeper levels of ecological understanding by facilitating a creative dialogue between children and nature. This study draws on local, indigenous traditions of “reading the landscape” to recontextualize the natural environment. Children will engage with plants and wildlife as co-researchers or “story-trackers'' to discover and create multi-modal narratives within a bird and pollinator habitat restoration project on the campus of their elementary school.

Methodology

-

Participatory action research operates from the assertion that those most affected by a social issue should be key players in any research process that seeks to understand the issue. (Ayala 1) This study uses an arts-based participatory action research methodology. Arts-based research can access information that is unmeasurable by more traditional forms of research (Eisner, 1997; Levy, 2017). By treating art forms as data, arts-based research brings forth that which is non observable and idiosyncratic (Eisner, 1981) as well as that which is imagined or transcends the limits of language and measurement (Muir, 2020). Artworks can be considered the primary data source or can complement conventional research methods for mixed method approaches (Muir, 2020; Levy, 2017). Arts-based participatory action research presents opportunities for the co-construction of knowledge in underrepresented communities (such as children) and can provide insight through artworks which express a variety of perceptions, emotions and cultural values (Rathwell and Armitage, 2016; Ayala, 2016; Jokela, et al., 2015; Lopez et al,, 2018).

-

Arts Based Perceptual Ecology (ABPE) is a research methodology developed by artist/biologist, Dr. Lee Ann Woolery for studying environmental issues and is well suited to this study. ABPE is a methodology for addressing a research question according to strict and replicable protocols, which I learned in a 6 week training course with Dr Woolery in the Fall of 2022. She described ABPE as the process of collecting data through visual imagery and mark making in response to direct experiences in the landscape, apart from any preconceptions of what the finished product will be. In this way the researcher is the instrument and the data reflects the researcher’s sensory experience. The research protocols provide a framework for seeing more than what is simply visible, by connecting what is seen to what is perceived on a subconscious, intuitive, imaginative level. Through this process, a language of place can be developed which documents the stories of the land (Woolery 2021).

-

Two classes of fourth-grade students will participate in the study as part of their regular bi-momthly garden/environmental literacy classes which are taught by myself, hereby referred to as the teacher -researcher and attended by their classroom teachers. The students, hereby referred to as student-researchers, have been working with the teacher-researcher on the planting and tending of native plants in the schoolyard habitat garden since the beginning of the current school year. The teacher -researcher will engage student-researchers in an arts-based participatory action research methodology to gather data in the habitat garden through arts-based perceptual ecology research protocols. Student -researchers will act as “story trackers'' to collect data in the form of drawings and paintings which will be compiled by student-researchers into digital visual narratives (cartoon, illustrated story) to be displayed on a website linked to the signage in the garden.

-

Student researchers will use the following Arts-Based Perceptual Ecology (ABPE) protocols to collect data or story fragments in the habitat garden.

Acoustic Ecology - sound maps

Graphic Facsimile - drawings/paintings from observation

Shadow Tracings

-

Student-researchers will use the data collected from the research protocols construct a visual narrative in the form of a stop-motion animated video. which will be uploaded to a page of the school website that will be displayed in the school garden.

-

Student-Researchers will use Visual Thinking Strategies (Yennawine, 1997) to construct meaning from the stories of their classmates.

Possible extension - student-researchers will conduct VTS with other students from other classesto uncover meaning in the stories.

Timeline

Phase 1

Data Collection at McNear Habitat Garden

March - April 2023

Phase 2

Synthesis of Data

May 2023

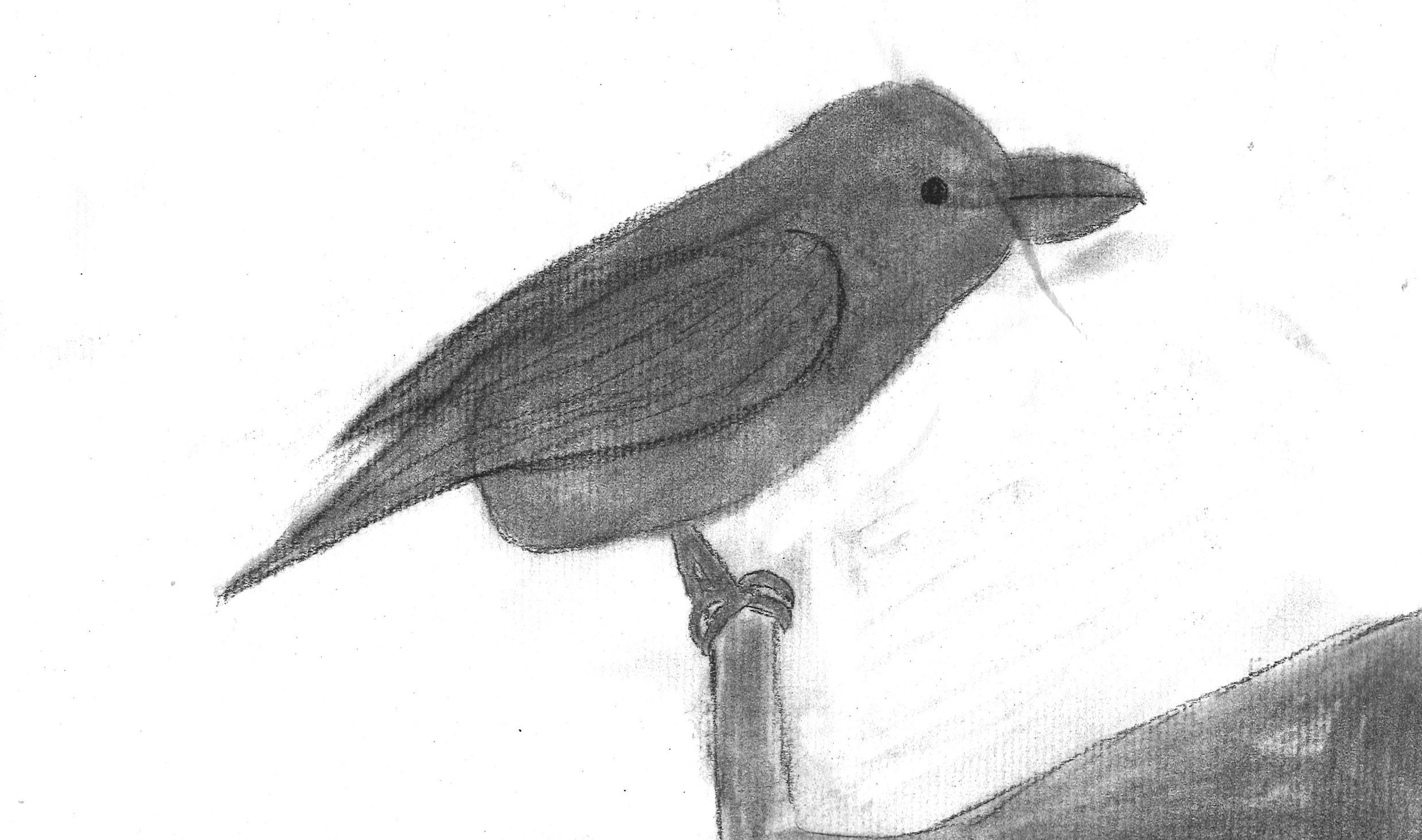

Student-researchers used the data from the above protocols to construct a multi-modal narrative related to their experience in the habitat garden. This process was framed by the Crow Sisters, Question Woman and Answer Woman, (Sarris, 2017) who tell stories through questions and answers. Students used drawings of the crow sisters as a graphic organizing tool which frames their narrative in inquiry .

Supporting Materials

Phase 3

Analysis of Data

June 2023

Student-Researchers used Visual Thinking Strategies (Yennawine, 1997) to construct meaning from the stories of their classmates.